Cilium

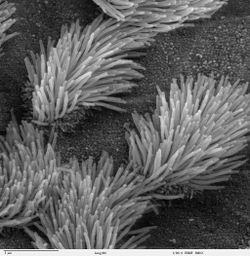

A cilium (plural cilia) is an organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Cilia are slender protuberances that project from the much larger cell body.[1]

There are two types of cilia: motile cilia and non-motile, or primary cilia, which typically serve as sensory organelles. In eukaryotes, cilia and flagella together make up a group of organelles known as undulipodia.[2] Eukaryotic cilia are structurally identical to Eukaryotic flagella, although distinctions are sometimes made according to function and/or length.[3]

Contents |

Types and distribution

In humans, primary cilia are found on nearly every cell in the body.[1] Cilia are rare in most plants, occurring most notably in cycads.

Ciliates are microscopic organisms that possess motile cilia exclusively and use them for either locomotion or to simply move liquid over their surface.

Larger eukaryotes, such as mammals, have motile cilia as well. Motile cilia are usually present on a cell's surface in large numbers and beat in coordinated waves. In humans, for example, motile cilia are found in the lining of the trachea (windpipe), where they sweep mucus and dirt out of the lungs. In female mammals, the beating of cilia in the Fallopian tubes moves the ovum from the ovary to the uterus.[4]

In comparison to motile cilia, non-motile (or primary) cilia usually occur one per cell; nearly all mammalian cells have a single non-motile primary cilium. In addition, examples of specialized primary cilia can be found in human sensory organs such as the eye and the nose. The outer segment of the rod photoreceptor cell in the human eye is connected to its cell body with a specialized non-motile cilium. The dendritic knob of the olfactory neuron, where the odorant receptors are located, also contains non-motile cilia (about 10 cilia per dendritic knob).

Although the primary cilium was discovered in 1898, it was largely ignored for a century. Only recently has great progress been made in understanding the function of the primary cilium. Until the 1990s, the prevailing view of the primary cilium was that it was merely a vestigial organelle, without important function.[1] Recent findings regarding its physiological roles in chemical sensation, signal transduction, and control of cell growth, have led scientists to acknowledge its importance in cell function, with the discovery of its role in diseases not previously recognized to involve the dysgenesis and dysfunction of cilia, such as polycystic kidney disease[5] congenital heart disease,[6] and an emerging group of genetic ciliopathies.[7] The primary cilium is now known to play an important role in the function of many human organs.[1] The current scientific understanding of primary cilia views them as "sensory cellular antennae that coordinate a large number of cellular signaling pathways, sometimes coupling the signaling to ciliary motility or alternatively to cell division and differentiation."[8]

Structure, assembly and maintenance, and function

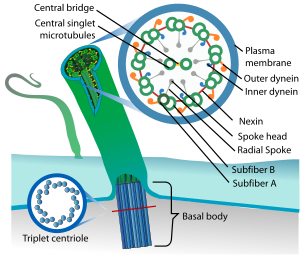

"Inside cilia and flagella is a microtubule-based cytoskeleton called the axoneme. The axoneme of primary cilia typically has a ring of nine outer microtubule doublets (called a 9+0 axoneme), and the axoneme of a motile cilium has two central microtubule singlets in addition to the nine outer doublets (called a 9+2 axoneme). The axonemal cytoskeleton acts as a scaffolding for various protein complexes and provides binding sites for molecular motor proteins such as kinesin II, that help carry proteins up and down the microtubules."[1]

The building blocks of the cilia such as tubulins and other partially assembled axonemal proteins are added to the ciliary tips which point away from the cell body. In most species bi-directional motility called intraflagellar transport or IFT plays an essential role to move these building materials from the cell body to the assembly site. IFT also carries the disassembled material to be recycled from the ciliary tip back to the cell body. By regulating the equilibrium between these two IFT processes, the length of cilia can be maintained dynamically. The disassembly of the cilia requires the action of the protein kinase Aurora A .[9]

Exceptions where IFT is not present include Plasmodium falciparum which is one of the species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans. In this parasite, cilia assemble in the cytoplasm.[10]

At the base of the cilium where the cilia attaches to the cell body is the microtubule organizing center, the basal body. Some basal body proteins as CEP164, ODF2 [11] and CEP170,[12] regulate the formation and the stability of the cilium. A transition zone between the basal body and the axoneme "serves as a docking station for intraflagellar transport and motor proteins."[1]

"In effect, the [cilium] is a nanomachine composed of perhaps over 600 proteins in molecular complexes, many of which also function independently as nanomachines."[8]

Sensing the extracellular environment

"Some epithelial cells are ciliated, and they commonly exist as a sheet of polarised cells forming a tube or tubule with cilia projecting into the lumen." Primary cilia on epithelial cells provide chemosensation, thermosensation and mechanosensation of the extracellular environment by playing "a sensory role mediating specific signalling cues, including soluble factors in the external cell environment, a secretory role in which a soluble protein is released to have an effect downstream of the fluid flow, and mediation of fluid flow if the cilia are motile."[13]

Ciliary defects can lead to a number of human diseases. Genetic mutations compromising the proper functioning of cilia, ciliopathies, can cause chronic disorders such as primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), nephronophthisis or Senior-Loken syndrome. In addition, a defect of the primary cilium in the renal tube cells can lead to polycystic kidney disease (PKD). In another genetic disorder called Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS), the mutant gene products are the components in the basal body and cilia.[7]

Lack of functional cilia in female Fallopian tubes can cause ectopic pregnancy. A fertilized ovum may not reach the uterus if the cilia are unable to move it there. In such a case, the ovum will implant in the Fallopian tubes, causing a tubal pregnancy, the most common form of ectopic pregnancy.

Since the flagellum of human sperm is actually a modified cilium, ciliary dysfunction can also be responsible for male infertility.[14]

Of interest, there is an association of primary ciliary dyskinesia with left-right anatomic abnormalities such as situs inversus (a combination of findings known as Kartagener's syndrome) and other heterotaxic defects. These left-right anatomic abnormalities can also result in congenital heart disease.[15] In fact, it has been shown that proper cilial function is responsible for the normal left-right asymmetry in mammals.[16]

Ciliopathy as an origin for many multi-symptom genetic diseases

Recent findings in genetic research have suggested that a large number of genetic disorders, both genetic syndromes and genetic diseases, that were not previously related in the medical literature, may be, in fact, highly related in the root cause of the widely-varying set of medical symptoms that are clinically visible in the disorder. These have been grouped as an emerging class of diseases called ciliopathies. The underlying cause may be a dysfunctional molecular mechanism in the primary cilia structures, organelles which are present in many diverse cellular types throughout the human body. Cilia defects adversely affect "numerous critical developmental signaling pathways" essential to cellular development and thus offer a plausible hypothesis for the often multi-symptom nature of a large set of syndromes and diseases.[7] Known ciliopathies include primary ciliary dyskinesia, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, polycystic kidney and liver disease, nephronophthisis, Alstrom syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome and some forms of retinal degeneration.[7][13]

See also

- Mucociliary clearance

- Kinocilium

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Gardiner, Mary Beth (September 2005). "The Importance of Being Cilia" (PDF). HHMI Bulletin (Howard Hughes Medical Institute) 18 (2). http://www.hhmi.org/bulletin/sept2005/features/cilia.html. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ A Dictionary of Biology , 2004, accessed 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Haimo LT, Rosenbaum JL (December 1981). "Cilia, flagella, and microtubules". J. Cell Biol. 91 (3 Pt 2): 125s–130s. doi:10.1083/jcb.91.3.125s. PMID 6459327.

- ↑ "Cilia in nature" (PDF). hitech-projects.com. 2007. http://www.hitech-projects.com/euprojects/artic/index/Cilia%20in%20nature.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ↑ Wagner CA (2008). "News from the cyst: insights into polycystic kidney disease". Journal of Nephrology 21 (1): 14–6. PMID 18264930. http://www.jnephrol.com/Article.action?cmd=navigate&urlkey=Public_Details&t=JN&uid=9A13E591-2E27-441B-8356-23BF86D9CFB0.

- ↑ Brueckner M (June 2007). "Heterotaxia, congenital heart disease, and primary ciliary dyskinesia". Circulation 115 (22): 2793–5. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699256. PMID 17548739.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N (2006). "The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7: 125–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Satir, Peter; Christensen, Søren T. (2008). "Structure and function of mammalian cilia". Histochemistry and Cell Biology 129 (6): 687. doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0416-9. PMID 18365235.

- ↑ Pugacheva EN, Jablonski SA, Hartman TR, Henske EP, Golemis EA (June 2007). "HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium". Cell 129 (7): 1351–63. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. PMID 17604723.

- ↑ Of cilia and silliness (more on Behe) - The Panda's Thumb

- ↑ Ishikawa H, Kubo A, Tsukita S, Tsukita S (May 2005). "Odf2-deficient mother centrioles lack distal/subdistal appendages and the ability to generate primary cilia". Nature Cell Biology 7 (5): 517–24. doi:10.1038/ncb1251. PMID 15852003.

- ↑ "Functional characterisation of the centrosomal protein Cep170". http://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/9783/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Adams, M; UM Smith, CV Logan, CA Johnson (2008). "Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies". Journal of Medical Genetics 45 (5): 257–267. doi:10.1136/jmg. PMID 18178628. http://jmg.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/45/5/257.

- ↑ Ichioka K, Kohei N, Okubo K, Nishiyama H, Terai A (July 2006). "Obstructive azoospermia associated with chronic sinopulmonary infection and situs inversus totalis". Urology 68 (1): 204.e5–7. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.072. PMID 16850538.

- ↑ Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, et al. (June 2007). "Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia". Circulation 115 (22): 2814–21. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. PMID 17515466.

- ↑ McGrath J, Brueckner M (August 2003). "Cilia are at the heart of vertebrate left-right asymmetry". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 13 (4): 385–92. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(03)00091-1. PMID 12888012.

External links

- Brief summary of importance of cilia to many organs in human physiology

- The Ciliary Proteome Web Page at Johns Hopkins

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||